From Wikipedia...

The American dipper inhabits the mountainous regions of Central America and western North America from Panama to Alaska. It is usually a permanent resident, moving slightly south or to lower elevations if necessary to find food or unfrozen water. The presence of this indicator species shows good water quality; it has vanished from some locations due to pollution or increased silt load in streams.

Also from Wikipedia, this is a picture of a North American Dipper:

Quite the dashing bird, really.

You might be wondering why an introductory piece on Coal Mining in the Eastern Slopes of Alberta is starting off with a clumsy if not dissonant introduction to the only aquatic songbird in North America.

It's a reasonable question.

I fell that I have to tell you though, the answer to that question is one that you'll have to wait a while for. We have some ground to cover before that particular narrative seed germinates and blooms.

Moving on…

In June of 2025 I spent a few days in the Crowsnest Pass.

It wasn't however, my first trip there.

Just a few years ago I made the trip down to the town of Coleman (a town in the Crowsnest Pass) to buy a 1982 Lebanon convertible for the bargain basement price of $500. I love that vehicle deeply and that alone is enough to endear the region to me, but my intermittent history with the Crowsnest Pass goes back much farther than self satirical automobile purchases.

I've been there many times before.

Frank Slide is deeply embedded in my childhood memories. When I was a kid growing up in Alberta, my parents used to take me on all kinds of camping trips across the province and Western Canada. My father, among many other things, is a biologist and a lepidopterist.

(That means he collects butterflies)

The "best" butterflies are often found in The Places Where People Generally Aren't, so I spent many summers being dragged across this mountain or that mountain in the pursuit of The Places That People Generally Aren't.

Which meant more than a few trips through the Crowsnest Pass.

I’m reasonably certain that somewhere, there are pictures of a much younger version of me scrambling up some of the massive boulders that were deposited in the aftermath of the rockslide at the townside of Frank. I’m also reasonably certain that I was taken in with the idea of a bank being buried in the slide.

There was no bank buried, that is an urban legend.

(That was an anecdote about not believing every little thing that you hear)

That is also my explanation as to how a semi-obscure disaster site has been imbedded in my subconscious from a very young age. Giant rocks and buried treasure.

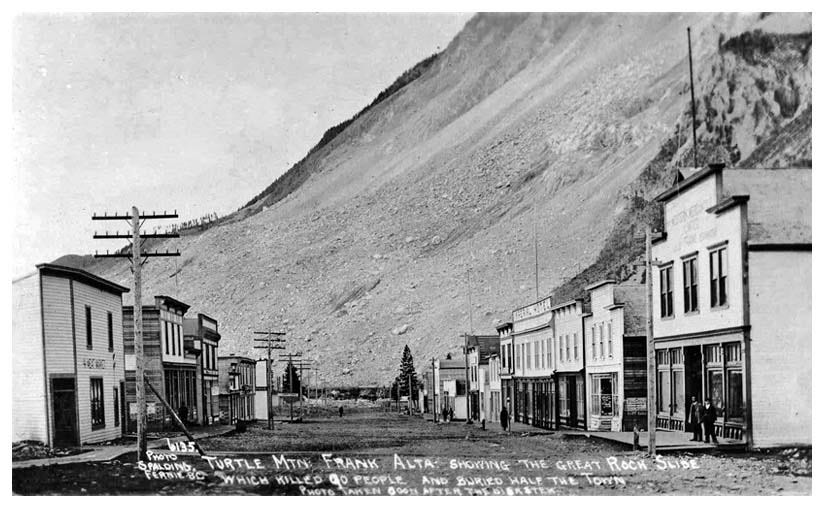

Nonetheless, If you're unfamiliar with the story of the town of Frank, here it is, albeit condensed for the exciting and relevant parts.

The town of Frank was incorporated in 1901 as something of a base camp community for the growing coal mining industry in the Crowsnest Pass. It has dozens of businesses a school and was a growing community immediately after it set down it's roots.

Of particular note, the town of Frank was established at the base of Turtle Mountain.

Of additional particular note is the fact that prior to the establishment of the town of Frank, it had a long oral history with the First Nation peoples of the area.

They did not call it "Turtle Mountain".

They called it "the mountain that moves".

(Roughly translated of course)

In fact, the mountain known to move was so well known to move by the First Nation People of the area that they refused to even camp at the base of it.

As it turns out, the mountain that moved had the somewhat unique characteristic of having a top layer of limestone supported by softer layers of sandstone and shale.

As it also turns out, when the town was being established, the First Nations peoples of the area tried to warn the people building the town that the mountain was known to move from time to time.

Their warnings went unheeded.

And so it came to pass that on April 29th, 1903 the mountain moved with so much noise and fury that it was heard as far away as Cochrane, almost 250 kilometers away.

Over 100 million tonnes of rock flew down the side of the mountain, crushing a good portion of the town of Frank and ending the lives of around 80 townsfolk.

The town rebounded for a brief period, but in 1917 the coal mine that the town had been built to support closed permanently and Frank was largely relegated to being a tourist attraction.

And for those willing to hear it, a cautionary tale.

In trying to find a way into the story of the problem of coal mines in the Eastern Slope, I like the story of the town of Frank.

For me, it is a story of greed trumping caution and reason against the protests and warning of those who knew the land and it's potential dangers much better than those looking to extract the lands wealth.

And at the core of the coal mine controversy in Alberta, that story is set to play out again, almost certainly with similar catastrophic results, except this time the unintended consequences that may be unleashed might not being limited to a historic landslide.

Instead, this story could very easily and very predictably end with the poisoning of the water supply for most of Southern Alberta.

This time though, the First Nations people don't stand alone in raising the alarm. The prospect of coal mining returning to the province of Alberta has been met with condemnation from an overwhelming number of Albertans, both rural and Albertans.

On it's face, it seems like this should be a relative no-brainer.

Don't mine the Eastern Slopes.

(Put that on a bumper sticker!)

But all indications are that once again, the relentless pursuit of pulling riches out of the ground is the proverbial trump card that overrides all reason.

Alberta premier Danielle Smith has made it clear that mining will go ahead, consequences be damned.

The long standing rumor of Smith's endgame is that she plans to retire to a Panamanian beach front after her inevitable second self immolation in the political arena anyways, so she's got minimal long game stock in the potential consequences, catastrophic though they may be.

But I digress…

As stated earlier, in June of 2025 I spent a few days in the Crowsnest pass. That trip wasn't the first time that I had tried to learn about the coal situation, but it was the first major step towards making whatever this is a reality.

Before heading down south, I had already completed several interviews with community members of Southern Alberta who were working to raise awareness of the massive risks involved with reporting coal mining in the Eastern Slopes through The Breakdown. I will refer to some of those interviews as we go, because much what those voices in those interviews had to say should be heard by all Albertans.

(And evidently some very very wealthy Australians, not that they would care all that much).

But the reality of the coal mining problem in Alberta is that it is so big and complex, in order for me to feel like the story so far has been told in a way that can be grasped, it needs to be written down. A 3 hour monologue simply won’t do here.

Alberta's coal mining problem is an environmental story. It's a legal story. It's a historical story that tracks right to the core of the identity of Canada. It's a story that has underdogs and on the flip side, a story that has oligarchs whose appetite for wealth is simply insatiable. It has politicians who will say whatever they feel needs to be said to justify their decisions but seemingly who will not use that same verbal contortionism to stand up for the long term interests of their province.

It's a multifaceted, complex nightmare of a story that can't possibly be explained or understood in a single sitting.

But let's see what we can and can’t do over the coming weeks and months anyways.

Not only a dashing bird but has a great little dance .

OK, so there wasn’t a bank. But was there not the mine payroll? That’s what I learned as a child. And the baby girl named Frank? She was real, wasn’t she?

And if I may digress even further, I have similar fond feelings for the area. If you check out the museum in the old school in I think Coleman, you will see a photograph of the first woman in Alberta to be hung and you will be introduced to numerous rum runners, many of whom seem to be from the Slocan Valley and of Russian extraction.

Clearly the entire area is a valley of stories and must become a UNESCO sacred site, pronto!